Peer Learning is...

The Coherence Question

Making Peer Learning part of an existing educational experience pays off in impact and operational efficiency.

Start a Hackathon to give everyone's side project a boost in momentum. Switch a lecture or two for a clinic session, and more local experts will join in, while the program manager saves time.

As education programs evolve though, they take on different goals. Learners change. Institutional agendas change. People come and go, and over time, initiatives turn into assumed process or tradition, separated from their original purpose. We forget why things are the way they are. Attempts to improve get constrained by "this is just how we do it". The promise of big changes usually get curtailed.

Both learners, educators and managers are in a position to reformulate. Leadership can be reasserted, not through directives, but rather through convening.

(Re)designing a peer learning environment

At this point, we have to go back to the drawing board. The challenges that the program faces can only be solved by re-introducing clarity about the program's purpose.

Is that MBA program teaching kids to get management jobs, or teaching experienced managers to improve? Is the startup accelerator trying to help local startups raise investment, or help local entrepreneurs build high-growth businesses?

There's a tension between institution goals, and with the goals set by the learners themselves. And within each of those there can also be strong divergence.

A simple question that leads this exploration and drives towards a unifying final answer is the Coherence Question:

What can we help people become?

Where do the institutional goals and learner goals align, and where don't they? What experience is available to make those goals viable?

Taking ownership of the Coherence Question reinstates leadership over the direction of the program, and clarifies strategy and implimentation issues. It encourages stakeholders to ask this question themselves, and engage with the redefinition process.

The Coherence Question relates to external positioning and internal alignment.

When you find agreement on the answer to this question, you're able to create a guiding policy for defining who you want in the program and how they apply. It defines how objectives are defined and what overall success criteria everyone can collaborate towards. The Coherence Question helps make sure all of these work in unison, and with proactive engagement from your organisation.

It also claims a competitive position, allowing everyone to direct resources to your programs' strengths.

Peer Learning provides new capabilities, allowing you to reframe your goals on your own terms. But applying Peer Learning techniques is often hindered by legacies in how we think about education.

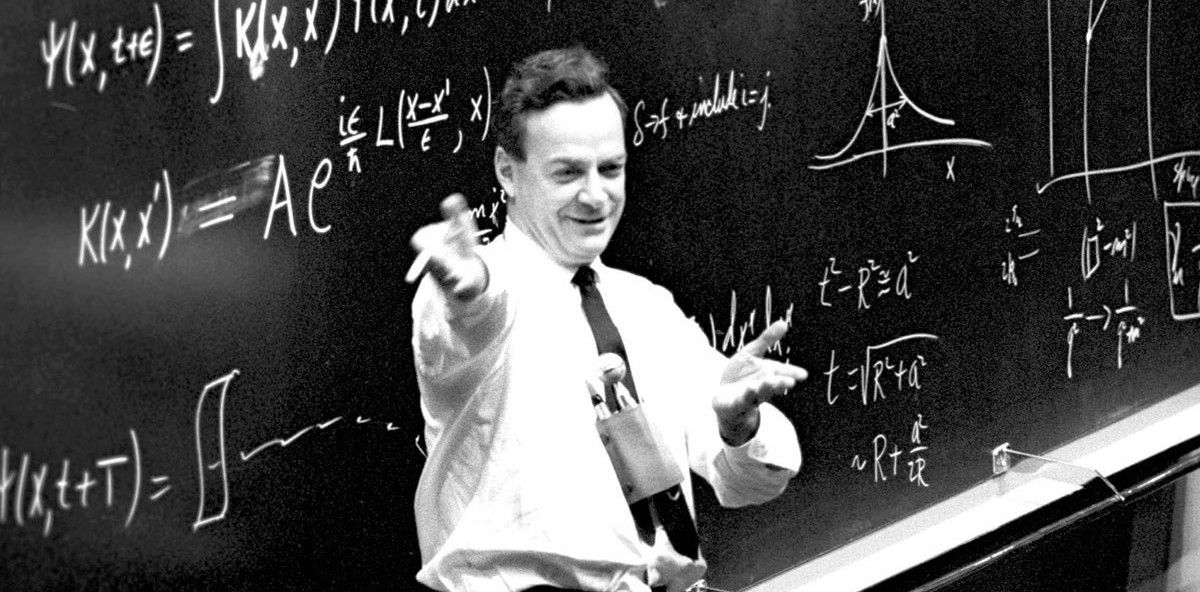

Content, methodologies and models, and the ways of operating education are all connected, and challenging assumptions in one usually expose assumptions with others. Henry Mintzberg started IMPM by questioning the case study methodology, but this lead to other questions:

You can’t train young people to be managers. So the starting point is nobody should get into any MBA program until they are in management positions and have decent proper experience. And then you don’t build those programs around a bunch of analytical techniques, although you obviously use those too, they’re useful. But you build the program primarily around them learning from their own experience.

Instead of attracting bright, young students with no experience, the IMPM program accepts only experienced managers. They've chosen a better path to pave, but they also haven't let the proliferation of the case study methodology dictate their goals.

Traditional education is based on an industrial methodologies, which puts a heavy requirement on defining prerequisites, educating in a repeatable way, and forcing everyone towards a single goal. A factory to create homogeneous, qualified worker bees.

Peer Learning requires none of these things, and actually benefits from joining people at different stages, educating in different ways and supporting a plurality of learning goals. This gives you flexibility when you need it most.

Programs that change their definitions dramatically, to move away from a singular model of "X to Y" path and towards an "enabling you to be better at Z", quickly claim and maintain leadership positions. They don't calcify around a topic definition. Instead, they work with what's available to them directly. Diversity and deviance from "the model" is no longer a concern in itself. Planned flexibility allows the program accomplish its goals in its own way.

Now is the time to question it all.

Assessment

We've found The Advice Process involves stakeholders well, without compromising design intent or the education team's sense of ownership.

Daniel Tenner, founder of Grant Tree, explains:

Anyone can make any decision they feel comfortable making. However, before they make that decision, they must ask those who will be impacted by that decision, and those who are experts on that subject, for advice. They are free to disregard the advice and make the decision the way they wanted to anyway, but they must first ask for advice.

To answer The Coherence Question with The Advice Process requires talking to stakeholders, raising the tensions and issues with them, and then asking them for advice. As this progresses, various possible answers arise and shift.

In the end, the primary goal isn't necessarily to find consensus, but to find an answer that will lead to a successful program that is backed by the institution.

The discussions that emerge from this question create coherent answers for (usually tricky but overlooked) implementation issues, like how or if to direct learners, how to attract learners and experts, and how to navigate internal agendas.

Learner's Goals

Diagnosing the educational environment involves researching learners' needs, assessing their alternatives and segmenting them into groups. In a typical situation, this would look like a competitive analysis, but as connectors, we're more interested in documenting their various goals and what knowledge sources are available.

Learners will ultimately find, and commit to objectives to work towards. The program is there to support them towards reaching those objectives, and success depends on the degree to which those objectives are achieved.

Answers to fundamental questions about the program design stem from who gets to define the objectives. Is it the program, or is it learners?

Aligned Objectives - should the program define a direction or range of objectives, and align learners towards it?

Distributed Objectives - will learners be better off defining their own objectives and participating in an education program that supports them?

Choosing between these isn't as obvious as it first seems, but this choice needs to be clear so that coherent success criteria for the whole program can be established.

Aligned objectives

When institutions have unique insight that warrant coordinating projects towards a common goal, the success criteria will be defined by that insight.

These type of objectives marshal people, and guide their time, and effort, and aligns them with what the program wants to achieve, but it's on the program to take responsibility for the validity of those objectives.

The Manhattan Project had a clear, military purpose, to be the first to build the atomic bomb. It provided the location and culture of multidisciplinary collaboration that attracted the brains to accomplish its goal. The institution had a higher-level insight that most of the individual contributors didn't, but in sharing that, everyone found a cause they believed in and a way to contribute to it.

The X Prize started in 1996 to inspire a non-government organization to launch a reusable manned spacecraft into space. Ten million dollars was offered to the first team that successfully launched twice within two weeks. It prompted more than $100M to be invested by competitors, and that goal was achieved in 2004.

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is a charity with a bigger aid budget than countries like Canada or Norway. They analyse development issues, like eradicating malaria, or improving nutrition. When a technology solution exists, but requires mass-coordinated effort for implementation, they use grant funding to rally the world's most talented people in these areas.

Programs designed to marshal people are aligned objectives focus on projects and offer extrinsic awards - such as prize money, titles or public recognition, or exclusive access to resources - based on performance targets or competition.

Decentralised objectives

When learners are specialists or have unique on-the-ground perspectives, they're often in the best position to define which objectives to pursue.

Entrepreneur First gives its participants compelling technology challenges from the business world to work on. From these challenges they know that their participants will distil a basis for defining their own startup project, as well as get their heads around the team composition to work in.

The Ashoka Foundation supports established social impact change-makers, people who are making early headway. Some fellows are even granted a stipend for a couple years, intended to support them to further explore and refine their model for impact. Ashoka supports its fellows to succeed at goals they set, to make their projects sustainable.

This category of program allows people to determine the objectives of their own projects.

Programs that support decentralised objects work best when they focus effort on intrinsic motivators, providing underlying support such as a supportive peer group, and financial sustainability.

Mixing objectives

Programs tend to struggle and fail when they mix these two types of objectives.

Most accelerators are familiar with the phenomenon of "accelerator tourists," people who are good at pitching their way into programs and stretch the funding to extend their stay rather than invest in their business. The extrinsic motivator, funding, is meant to push the founders towards an aligned objective of business progress, but the founders intrinsic motivations don't lie in that direction.

The Africa Prize had an underlying institutional goal, to build PR for the organisation. They invested in a PR agency and focused their final judging criteria on projects that made great news stories over those that had accelerated towards their social impact. The NGO wasn't in a position to set goals for the entrepreneurs; they knew better what needs to address and how to go about it. They are in the best position to set their objectives and in such cases, program's need to be careful to support those agendas rather than redirect them. But The Africa Prize offered extrinsic motivation, the prize money, and though it was never stated to the participants, they all worked out that only the "sad African stories for the BBC" could win. The result is that the winners often fail with their innovations, but go onto win other prizes and accolades, while some who fail to win grant money go onto create viable businesses.

Available experience

Considering all the diverse paths of learners, what experience and knowledge are available to draw on?

Established experts and consultants are an obvious starting point. They'll be prepared and motivated. They'll often be generalists with less hands-on experience, but with awareness of best practices.

Informal groups - meetups, clubs, study groups - will have more hands-on experience, and can shed light on practical problems. While they might not have easily-added workshops and presentors, they will have a wider range of experienced people who can help.

There are also other more non-obvious sources of knowledge around. They come in the form of experience of the doers in your locality, local business owners, artists, politicians or Rotary Club members, etc. These groups often reveal role models that your program can build on.

For the people that are not in your locality, you can look to involving specific role models from outside. If you have some project budget you could fly them in for a conference or talk, but deeper influence comes from a range of formats, like podcasts from conversations with them, blog posts, or Ask Me Anything session.

Some learners' challenges will be specific, requiring single experts to solve, while others will be novel, requiring a wider group to come together to untangle. Researching both types of needs and the people you'll call on to help will give you a bigger toolset to work with, making your redesign more applicable to learner needs.

When we need to run programs in new cities, we ask local co-working managers and bloggers about the local rising stars. Usually, they're not given a pedestal, so by putting the spotlight on them, our events attract and expose even more local expertise to share.

Insitutional and internal agendas

Assessing institutional goals requires more than following pre-written directives and mission statements.

Consider also:

- Where budgets and resources are allocated, and which budgets are being increased or decreased. This reveals another perspective on the institution's goals.

- Which past projects are celebrated, and why

- Internal agendas and ambitions of the program and institutional management

- The institution's funders, their explicit goals, funding changes and internal agendas

- The general goals of the community that surrounds the institution

Understanding colleagues ambitions and strategies, both outside of your program and beyond the educational goals, reveals internal factors that create risk to your program's execution. Some examples: some university departments compete with others for lucrative students. Most NGOs are driven by fund-raising activities, just as many prioritise PR over impact.

These need to be understood and catered for when answering The Coherence Question.

Coherence between the program's objectives and the selection of its participants will be a major factor in the effectiveness of a program.

Access by application

When you have a broadly-appealing offer, opening the program to applications allows you to focus effort on promotion, which generally makes a broader range of candidates aware.

Selecting candidates from a written application, or a short pitch, is prone to error, so this approach is appropriate when choosing some inappropriate candidates won't be too costly.

Y Combinator and Harvard use this approach well, because they've developed such strong reputations, they can attract the best.

Access by nomination

If it's important that every candidate is well-screened, or selection criteria are difficult to make consistent, an invitation-only method is more appropriate. This doesn't necessarily need to be done internally. Entrusting a network of nominators, even program alumni, often suffices.

This works best when you want to limit selection to self-directed people, since it's harder to spot good candidates who aren't already making visible progress.

The trade-off is usually one of diversity, as these programs tend to expand through high-trust social networks, which tend to be similar people.

Ashoka and Pirate Summit use this approach well, since they have strong ambassador networks aligned to their goals.

Open access

Offering open access to some low- or no-cost form of support opens your pipeline to a wider range of people. Tracking progress among them then becomes an opportunity to select the best, and invite them to participate in deeper support.

Startup Weekends allow people to experience a startup project in two days. Most people enjoy them, but don't become entrepreneurs. Though, it's also common for a few people to leave Startup Weekend with an idea they want to pursue.

This approach makes sense when it's important to choose only dedicated candidates but you need to allow people to develop themselves before they're ready. It also works well when learners have low agency and need a safe, low-commitment way to understand if they want to engage in a deeper program.

Concluding assessment

With an understanding of learners, their goals, and the niche local advantages, we're in a position to answer The Coherence Question.

Daniel Tenner explains how the Advice Process is used for research, not for building consensus:

This is about getting feedback/input into your decision, not about building consensus. Do not use the advice process to try and browbeat people into agreement or to build political support for your decision. You don’t need people to agree. You don’t need political support. You just need input to make sure that you make the right decision.

In the end, a program is better designed by a small group of people who have the experience to make effective decisions, and the commitment to see the program through. So if your final decision isn't aligned with the advice of some stakeholders, that's your call, but you'll have to explain why.

Over conversations with different stakeholders, a number of viable answers might have come up. For example, different stakeholders for an enterepeneurship support program might have been suggested:

- We help inventors to commercialise

- We help academic researchers become licensors

- We help innovators become entrepreneurs

- We help foreign innovators commercialise in our country

These are generally aligned, but also have critical divergences that need addressing.

For example, should the program be designed for specific types of commercialisation (becoming an entrepreneur and commercialising an invention yourself, or finding a licensing deal for another company to do the commercialisation) or both? This can be answered by looking at learners' goals, institutional goals and what available expertise might make each path viable.

This could be resolved by selecting one (Licensing only, since we don't have good entrepreneurial role models available) or generalising (We support any commercialisation path the learner chooses, since our organisation is primarily responsible for enabling engineers.)

Another tension here arises out of the definition of who the program should be designed for. Innovators is the broadest definition, but possibly too broad to make a program relevant to everyone. Academic researchers reveals a community that stakeholder is prioritising, which indicates they will only support initiatives that support that group, and may informally steer resources towards that group of learners and away from others.

The fourth potential answer indicates a politically-motivated agenda, possibly arising from funders or supporting community interests. If it's the case that this indicates an unexplicit policy, then it will be have to be included.

In this case, the final answer to the Coherence Question was: We support foreign innovators, selected by our partners, to commercialise globally through UK relationships.

This resolves most of the tensions by deferring to the learners' goals. If they want to explore entrepreneurship, crowdfunding, or UK licensing markets, that's their choice and we'll help. But the program will focus on options that make the most of the UK network we can bring to their aid.

It also leads to a specific success criterion: how many were actively commercialising through a UK connection after the program concluded?

Parameters and tactics

Having a viable and desirable answer to the Coherence Question, our attention now turns to design and implementation. What do we have to work with? Is our ambition in line with our means? What program design will give us the best chances of success?

To get practical, use the parameters of time and money to frame the scope of the design.

Money

Budget is often considered the main constraint in program effectiveness, but usually this is because the scope of operations pushes the limits of the budget. After all, why not strain to get the most out of your money?

The assumption that educational programs are basically events, workshops and lectures, sets an expectation that the amount of money dictates the length of program. If your budget is $10,000 and workshops cost $1,000 per day, then the trap is to assume that the program has to be limited to something like 10 days or less.

Peer Learning is outcome focused, so it's cost-effectiveness is measured in outcomes, not teaching time.

Programs that are designed to work effectively within a budget, rather than push the budget, end up focusing on efficiency rather than volume. They consider educational activities as investments with a future return, not costs to be managed. In practice, this shifts towards investing in communities that scale to needs without additional costs or management time. They shift away from activities with high marginal costs, like expensive trainers and venues. They achieve more with less because they invest in community as an asset, and they build on what actually works.

Time

Most educational programs are rigid in time commitment required by the students. The program dictates the program length and schedule, and then learners need to adapt. But now that we've put the learner's objectives on centre stage, the consideration of time, and length of the program switches to them.

Consider the learners' goals - how long does it normally take people to achieve those goals? And consider the learners' life and environments - what timeframe and level of intensity is sustainable for them? Use these as indicators for an ideal duration and schedule.

On the other hand there is also the factor of availability of the people that support the program. What is workable for them? Regular small interventions, with little preparation required are an easier ask to commit to for contributors, than larger chunks of time that need more preparation.

As for the duration of the activities themselves, it's better to ask what's the shortest they can be, rather how long they need to be. Rather than plan plenaries that keep everyone waiting for the group to progress, look at plenaries for short bursts and grouping activities. These allow self-paced learning to happen at a steady rate outside of the pre-planned activities.

If you have a clear idea of the length of the program, the activities, and the time requirements regarding the supporting team, Peer learning allows you to use more community and voluntary expertise to achieve better results, while keep surplus budgets available for ad-hoc opportunities or longer-term investments.

A guiding policy

Your answer to the Coherence Question provides a simple, understandble guiding policy for creating an effective learning environment.

Combined with a shift towards peer learning roles and responsibilities, it:

- creates financial and operational efficiencies, based on measureable outcomes

- let's everyone in and around the program self-direct towards an aligned goal

- shifts attention and effort towards longer-term gains and positioningPeer Learning disciplines: curation, facilitation, conveningPeer learning moves the emphasis off subject expertise and onto community development, which means thinking of team skills in relation to event operations, facilitation and network-building. For example, if there’s a lack of advertising skill to recruit applicants, building a community through even…

Your answer to The Coherence Question defines success criteria, based on the number of people you can enable or transform.

With that, you're able to choose the most appropriate learning formats that increase agency, responsiveness, and connectivity. This, in turn, enables you to design a cyclical program schedule and assign the team it's roles and responsibilities to animate it. And you can decide on banner topics, together attracting innovators, promoters or performers to build your community.